If George Beal, Curtis Besinger, and Eugene George were the fathers of KU’s modern architecture program, then Professor Emeritus Stephen Grabow, who died last week in Bloomington, Minn. at age 81, was its passionate, steadfast defender.

Separated by one or two degrees from Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Gropius, who strongly influenced the development of the architecture department’s modern curriculum, Grabow was hired by and taught alongside Besinger, a key figure in Wright’s Taliesin school.

From 1973 until his retirement in 2017, Grabow played a leading role in elevating the prestige of the KU School of Architecture, especially through his creation of study abroad programs and recruitment of faculty talent. His imprint on students, many of whom are now shaping our built environment, is incalculable.

In 2015, our paths crossed when I took his monumental Principles of Modern Architecture lecture. Though I wasn’t an architecture student—I took the class because of my involvement with Lawrence Modern and interest in modern architecture—I remember going into Marvin Hall Forum, the Studio 804 addition where the lecture was held, thinking I knew something about the subject. I was wrong. I had barely scratched the surface. Week after week, I walked out of class feeling like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz when she went from black and white to Technicolor. The outside world seemed utterly transformed. Aside from a sociology class I took in my freshman year of college, no other academic course I’ve taken has had as big an impact.

Prof. Grabow was a superb lecturer. I can still see him wandering around the room, leaning against the louvered glass walls, his arms folded, his fingers rubbing his chin in thought as he brilliantly deconstructed hundreds of buildings and artworks in his slide decks, adding insightful context drawn from his immense knowledge of liberal arts and worldly cultures. Through his intellectual curiosity and layered storytelling, modern architecture came across as a far more complex activity than I had previously imagined, much more difficult and profound than any of the individual arts like sculpture or painting, for example.

Grabow lectured that modern architecture isn’t a style, it’s a paradigm. Its original intent was to serve humanity upended by the horrors of industrialization. To that end, buildings shouldn’t just shelter you, they need to contribute to your well-being. He showed us what he considered some of the great modern buildings that took that social and functional imperative seriously, such as Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin office building, the Berlin Philharmonic concert hall, Louis Kahn’s Trenton Bath House, the Halen Estate housing complex by Atelier 5 architects, among many other examples.

Through his lectures, we learned that when guided by modern architectural principles an office building can be as worthy a space as a church, and that a bathhouse or playground can be as significant a work of architecture as a museum or library. We also learned that the most profound buildings in architectural history have a deep functional concept behind them. They’re not just disposable scenery.

Indeed, Prof. Grabow believed that for architects, functional design was the most challenging and interesting part of architectural design—it’s where the creativity comes from, he said—and the hardest to master. Transcending the “program” and turning it into something more meaningful—making it poetic—is what makes architecture an art. Accordingly, he hated avant-garde architecture, not only because its proponents—architects like Frank Gehry and firms like Coop Himmelblau—trash functionalism and the early modernists but also out of his frustration that the avant-garde so easily seduces young students of architecture.

“It’s like drugs,” I remember him saying.

To guard young minds from falling into that tempting trap, he expected students—most of them freshmen and sophomores—to show up and pay attention. Remarking on a previous mid-semester lecture with many absentees, he reminded students attending how fortunate they were to be in a school that turns away six students for every one they accept. He told them bluntly, “You’re taking up someone’s space if you’re not serious about this material.”

At my comfortable remove from the stakes of the profession—I was 50 when I took the class—I found Grabow’s strict, business-like manner refreshing and his self-effacing cynicism endearing. In hindsight, they were premonitions of his early retirement.

One giveaway was his last lecture, where he unexpectedly veered off on a rant against commercial advertising, which he argued has infiltrated architectural design by emphasizing visual appeal over function. This has led to a false form of creativity, he said, and an excuse for students not to do highly disciplined architecture, which is much more difficult. He might have given the same talk year after year; but this one was personal, like a coach hinting that he’s ready to leave the field.

Soon after the class was finished, I moved to Los Angeles for work and didn’t see Steve again until 2022, when my wife and I dropped by his house to pick up some Danish modern furniture he was selling. (Steve was in the process of relocating to Minnesota to live near his daughter.) He told me that he was ready to leave Lawrence. He felt the town had changed a lot, most of the people he was close to had either left or died, and he was, as he said, “probably my oldest friend, which is a strange thing to happen to you.”

Despite being stressed about moving and coming out of several recent surgeries, Steve couldn’t have been kinder and more generous with his time. He gave us a full tour of his townhome, which looked like something architect Paul Rudolph would have loved, with huge wall mirrors, all-black rooms, artworks illuminated by individual track lights, and extensive shelving of vinyl LPs and CDs. We talked for a while about classical music, what he was doing to unload his massive record collection, Lawrence Modern, the latest Studio 804 project, and golf.

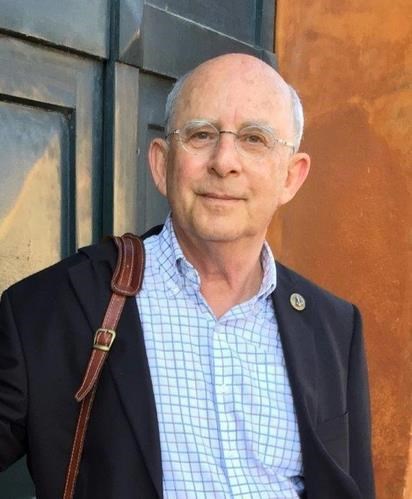

To my surprise, I learned that Steve was a low handicapper and the captain of his golf team in high school, as was I. (And like me, he watched golf on TV all the time and didn’t find it boring.) His wife was from Scotland, and while he taught arts education at the University of Dundee for a year, he got to play many of the great courses at the home of golf. He told me one time while he was playing Carnoustie outside of Edinburgh it was so windy that when he hit a wedge to the green the ball landed behind him. His telling of the story was humorously Grabow-esque, in that inimitable New York street-smarts mixed with book-smarts voice of his, as anyone who knew Steve would remember. I sensed it might be the last time I would see him, so just before I got up to leave, I took a photo of him on his sofa. I’m glad I did, because I will cherish the memory of Steve Grabow for as long as I live.

—Bill Steele

Stephen Grabow obituary. A memorial service will be held at Milton’s Cafe in downtown Lawrence on April 12 from 3-5 p.m.

Prof. Grabow’s talk at the Beal House gathering in 2015 on YouTube. Many thanks to Lisa Purdon!

One Comment

I absolutely loved this article of Steven Grabow.

LikeLike